Alberto Santos-Dumont, Dirigibles and Dinosaurs

725/04/2013 by noonobservation

I have recently become enamoured of the dirigible – that evolutionary dinosaur of aviation. Like the diplodocus, dirigibles were huge, slow, difficult to handle in high winds, and you needed massive, massive sheds to keep them in. They were also both made extinct by catastrophic explosions.

Airships (like dinosaurs) are of course extremely far-fetched and live in the same mental box as unicorns, time machines, robots and giant lasers that can destroy the Sun. Having studied the evidence however, I am now convinced they did exist, due partly to this man:

Alberto Santos-Dumont

Alberto Santos-Dumont was the heir to a Brazilian coffee fortune. An avid reader of H. G. Wells, he grew up in the happy belief that airships had already been invented.

When he was 18, his father gave Santos (as he was called) a cheque book and advised him to, “Go to Paris; the most dangerous of cities for a young fellow. Let us see if you can make a man of yourself.”

On his arrival, Santos was disappointed to find that there were no dirigibles. He was forced to settle for crappy spherical hydrogen balloons and the heady thrills of motor-tricycle racing.

Balloon technology

The problem with spherical balloons was that they did up and down okay, but sideways movement depended on the wind. On one jolly over central Paris, Santos and his four passengers were becalmed and had to jettison their luncheon basket, camp stools and two Kodak cameras to avoid falling onto the pointy houses.

An attempt at a powered balloon had been made in 1852 by Henri Giffard, using an extremely heavy and rather flamy coal-powered steam engine attached to an elongated hydrogen gas bag.

Though he miraculously succeeded in not blowing himself up, Giffard’s engine was too weak to fly against the wind. Subsequent attempts to build a steerable airship had ended in dismal failure and/or grizzly death.

Santos saw hope in his tricycle’s small, reliable petrol engine.

The Santos-Dumont No.1 had extra long suspension cords to keep the hydrogen and the burning petrol a respectable distance apart.

First powered flight

The Santos-Dumont No.1 first flew on September 20th 1898. Made from varnished yellow Japanese silk, wicker basket and 3.5 horsepower tricycle engine, the ship looked rather like a large, friendly caterpillar tied to a picnic. A crowd gathered at the Jardin d’Acclimatation, anticipating either the first successful powered flight or a gruesome, fiery accident: either way, a proper day out.

Dressed in a pin-striped suit, heeled shoes and panama hat, “Le Petit Santos” (who was 5’4” and weighed less than 8 stone) mounted the basket. The ship rose, cleared the trees and successfully manoeuvred a figure eight, making clear headway against the wind.

However, as the balloon descended, the hydrogen contracted, causing the envelope to collapse in the centre. Plummeting deathwards, Santos called out to some boys flying kites, urging them to take hold of his long guide rope and run into the wind. In this way, he succeeded in avoiding a “bad shaking-up.”

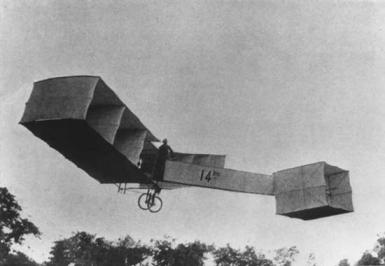

Flushed with success, Santos now experimented with new designs, the silliest being the Santos-Dumont No.4: To save weight (and for bonus eccentricity points) he replaced the wicker basket with a bicycle frame and used the peddles and handlebars to control the ship, prompting one aeronaut to say that he appeared to be riding “on a stick like a witch.”

(Interestingly, the French government had previously had to issue a pamphlet explaining to the rural peasantry that balloons were not in fact powered by dark magic and should not be torn apart on landing.)

The Deutsch Prize

In 1900, oil baron and airship fancier, Henry Deutsch, offered 100,000 francs to the first man to fly from Saint Cloud, round the Eiffel Tower and back again within 30 minutes. Paris spent 1901 watching Santos try for the prize.

His first attempt ended in Edmond de Rothschild’s chestnut tree. While Santos waited to be rescued, a servant climbed up with a luncheon basket and drinks invitation from Princess Isabel of Brazil who lived next door.

The second attempt ended on the roof of a Trocadero hotel. After Santos was rescued by the fire brigade, Mr Deutsch begged him not to try again.

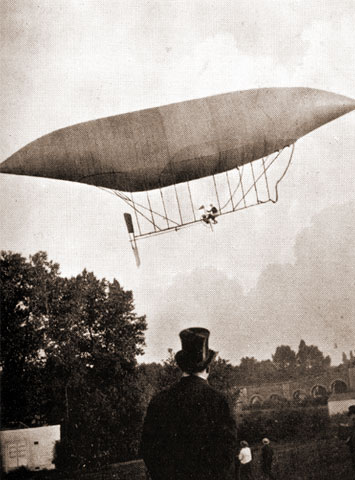

But on October 19th, the Santos-Dumont No.6 was readied.

This time, despite the engine stalling three times on the way back from the Tower, the No.6 returned safely after 29 minutes and 15 seconds.

On landing Santos shouted “Have I won?” The crowd replied, “Yes!” He was showered with flowers and presented with a cup of Brazilian coffee and a small white rabbit (the French are a mysterious people).

He divided the prize money between the poor of Paris and his own workmen, saying that he did not compete for money.

Living the dream

Alberto Santos-Dumont was now the most popular man in Paris and one of the most famous men in the world. The toy to have was the model Santos-Dumont No.6, the cake to eat was the gingerbread Santos-Dumont effigy, and the hat to wear was the one with the Santos-Dumont veil, covered in tiny appliqué airships.

After trips to Monaco, London and the White House, Santos returned to Paris in 1902, determined to prove that airships could be practical, everyday vehicles, and not just a means of keeping the fast-breeding population of amateur scientists in check.

The result was the Santos-Dumont No.9: a convenient little, 7,700 cubic foot dirigible for the man about town. Santos flew it to the shops, to cafés, and once to his apartment off the Champs Elysée. The spectacle caused major traffic jams, as did the 132 foot guide rope that dragged behind the ship, spooking horses and getting caught on cars, trees and pedestrians.

Santos dreamed of “the time, sure to come, when the owners of handy little airships will not be obliged to land in the street, but will have their guide ropes caught by their domestics on their own roof gardens.” Parking in Paris has always been tough.

Private Life

In 1902, the New York Mail sent a reporter to Paris to find out more about Santos-Dumont. Having gained access to his apartment, they reported back the shocking truth about his secret addiction:

Santos was addicted to knitting, embroidery and “all the light bits of needlework that are supposed to belong exclusively to femininity.” The horrified reporter described his interior decor as “the luxury of a pampered beauty rather than the gorgeous surroundings of a bachelor of wealth.” Lacy curtains, pink silks and huge satin bows were not considered quite the thing for heroic aeronautical pioneers, nor was Santos’s fastidious dress or his liking for bejewelled tie pins.

Another matter of concern, at least to the American press, was Santos’ indifference to women. Though adored by the ladies of Paris, they complained that he had nothing to say to them that wasn’t related to aeronautics. He often hosted “aerial” dinner parties using his seven-foot-high dinner table and matching chairs (which guest mounted using a ladder), but rarely conversed with anyone except the artist, Sem and his own workmen.

Heavier-than-air flying

Disheartened at the utter lack of dirigible competition, Santos entered the race to build the first heavier-than-air craft (or “aeroplane” as some people like to call them). The Bird of Prey successfully flew some 60 metres in October 1906. At the time, this was the first verified powered flight, and would have secured Santos scientific superstardom, had not the secretive Wright brothers suddenly revealed that they’d been flying for three years without telling anyone.

Disheartened at the utter lack of dirigible competition, Santos entered the race to build the first heavier-than-air craft (or “aeroplane” as some people like to call them). The Bird of Prey successfully flew some 60 metres in October 1906. At the time, this was the first verified powered flight, and would have secured Santos scientific superstardom, had not the secretive Wright brothers suddenly revealed that they’d been flying for three years without telling anyone.

Madness and death

After a bad crash in 1910, Santos was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and never flew again. He moved to a French seaside village and took up astronomy, with the result that locals accused him of spying for the Germans. Horrified by the indignity, Santos burned all his notes on flying and returned to Brazil.

Santos-Dumont had always believed that aircraft would bring about world peace. The First World War was a bit of a blow on that front and he held himself personally responsible for every death caused by a plane.

Santos-Dumont had always believed that aircraft would bring about world peace. The First World War was a bit of a blow on that front and he held himself personally responsible for every death caused by a plane.

In the 1920s he spent increasing amounts of time in Alpine sanatoriums, where he attempted to invent an engine that could push skiers uphill, patented a primitive greyhound racing lure, and tried to jump out of a window after gluing feathers to his arms. He also found the time to dig his own grave in São Paulo.

Feeling better, he returned to Brazil in 1928. The government sent a delegation of top scientists to welcome him on a plane christened the Santos-Dumont… which unfortunately exploded, killing everyone on board. Santos slid back into depression.

The final straw came in 1932, during Brazil’s Constitutionalist Revolution, when a plane passed over the hotel Santos was staying at and dropped a bomb nearby. Racked with guilt, Santos excused himself, went up to his room and hanged himself using two red silk ties.

Conclusion

Alberto Santos-Dumont was a man of vision. He believed that air travel would be as personal and convenient as travelling by car. He was not alone – Manfred von Richthofen thought the future of flight would be small, personal flying suits, not giant airliners.

Alberto Santos-Dumont was a man of vision. He believed that air travel would be as personal and convenient as travelling by car. He was not alone – Manfred von Richthofen thought the future of flight would be small, personal flying suits, not giant airliners.

Like evolution, technological progress can spiral off in unexpected directions, some of which end in flamy death. If we were all flying around in our personal dirigibles today, we would remember Santos-Dumont as he is still remembered in Brazil – as a hero, visionary and the most stylish man in aviation.

Some fascinating facts that wouldn’t fit

1. Santos once lent No.9 to a Cuban-American society girl named Aida Acosta. She remains the only woman to pilot a dirigible solo.

2. To overcome the difficulty of using a pocket watch while flying, Santos’s friend Mr Cartier designed for him the first civilian wristwatch. Cartier still sell the Santos-Dumont watch to the ridiculously wealthy.

3. The mortician who embalmed Santos secretly removed his heart and kept it in a jar of formaldehyde for 12 years before ‘fessing up.

Memorability spectrum

Hotness (Red): 82. No wives or confirmed lovers, so not a high score. The ladies liked him, but he probably batted covertly for the other side (if he batted at all).

Eccentricity (Green): 222. Spent his early life building and flying craft that everyone thought would explode. Spent his later life being crazy and depressed.

Violence (Blue): 32. Camp pacifist.

Edifying, enchanting, and inspiring, as usual. Actually, we have a plan. To fly a balloon to the edge of space. Alas, full of helium, and unmanned, and not powered, and so not as exciting / dangerous/ attractive, as Alberto Santos Dumont’s.

brilliant.

Airship No4 looks like his moustache!

I hadn’t noticed that. And I rarely fail to notice a moustache.

[…] manufactured in Paris by Henri Lachambre, (who also made balloons for Santos-Dumont) and delivered untested to Svalbard in 1896. When Andrée’s crew-mate Nils Ekholm inflated […]

Where are the dinosaurs?

They appear briefly as a simile in the introduction.

[…] airship, named the America, was built for him in France with guidance from Santos-Dumont and several French aeronauts. At 6,300 cubic metres, it was the second largest balloon in the world […]